It’s Saturday, March 14. I’m having a normal day. Coffee. Scrolling through posts on my phone — first in one app, then another, then again in the first app as if I hadn’t just done that very thing minutes before. It is the first normal day after so many not normal days that it feels decadent, like chocolate ganache in the form of minutes. The hours stretch out before me as if to tease me, as if to say, See how time is all in your head and how your fortune isn’t really up to you?

I watch television, I take a bath, I drink sparkling wine. I rest. I read. I worry. I think quietly about gratitude and luck. I pet my dogs. I try to savor the normal while I have it in my hands. Before I love it to death.

[][][]

Monday, March 2, was a normal day. We had a normal dinner and went to bed at the normal time. After midnight Holden appeared beside our bed and said something about how lightning and thunder had woken him up. I took my earplugs out and walked him back to his bed. As my ears adjusted, I realized the thrashing noise I was hearing was not a dream remnant or some sort of pressure equalization; it was the sound of rain and hail attacking the windows — aggressive and disorienting. I went back to my nightstand, picked up my phone, and went to Twitter — straight to the Nashville Severe Wx feed — and saw this tweet:

I rounded up the boys and the dogs and herded us into the basement, where we sat while I refreshed the feed over and over again until I could confirm the tornado had passed. We shuffled back up the stairs. We still had power. Things had blown off our porch and in our neighbors’ yards but I couldn’t see any trees down. I hadn’t even heard sirens or gotten a storm alert on my phone. I tucked Holden back into bed and put my earplugs back in and fell back asleep.

Around 5:30, I woke up to a deluge of panicked texts from all over — ARE YOU OK? WE SAW THE WEATHER REPORT, ARE Y’ALL OK? — and a notification that school was canceled. Then I went online. I started to see the photos of the places just down the street, places I drive by every day, local staples — leveled. My gut seized up as I recognized demolished structures near where my friends lived. I started sending out my own panicked texts and waiting for those three dots to appear in reply.

Then in came the texts from my supervisor about coming to the office as soon as possible. We had been activated.

[][][]

On a normal day, Hands On Nashville helps connect people who want to give back with opportunities in the community to do so. We work with nonprofit partners to publicize their volunteer needs, and we have programming to help nonprofits rethink how they can utilize volunteers. As the director of communications, my world is largely email blasts, PowerPoints, graphic design, quotes for media releases, social media posts, grant edits, and key messages. I joke that we get to do the fun stuff in the nonprofit world. We work with the people who want to make the world a better place.

HON is also the named partner for volunteer activation and management in Metro Nashville’s Comprehensive Emergency Management Plan. Meaning when a disaster is declared, we pivot full-scale to leading volunteer activation for the city.

Normal for us, for our city, ended on March 2.

[][][]

The morning of March 3, I leave Holden at home with Richard. The drive to the office takes an hour and a half. It’s normally about a 15-minute commute, a lovely one through Shelby Park where we usually see deer grazing. In the hours after the tornado, it’s not immediately clear what’s accessible or impassable so every route I attempt meets a dead end. Emergency crews, limbs down, yellow tape.

My heart is pounding and I’m starting to panic. I have to turn around again and again. Traffic is backed up everywhere I turn. It’s hard to know who’s got to be somewhere and who’s just out looking around. I don’t want to be someone who’s just in the way but I surely am with all these false starts, I think. My phone’s GPS stops working, so I can’t seek out smaller, less familiar alternate routes than the ones I’m used to using. I briefly panic that I will never find my way out or back home. I call my husband and try not to cry. I cry.

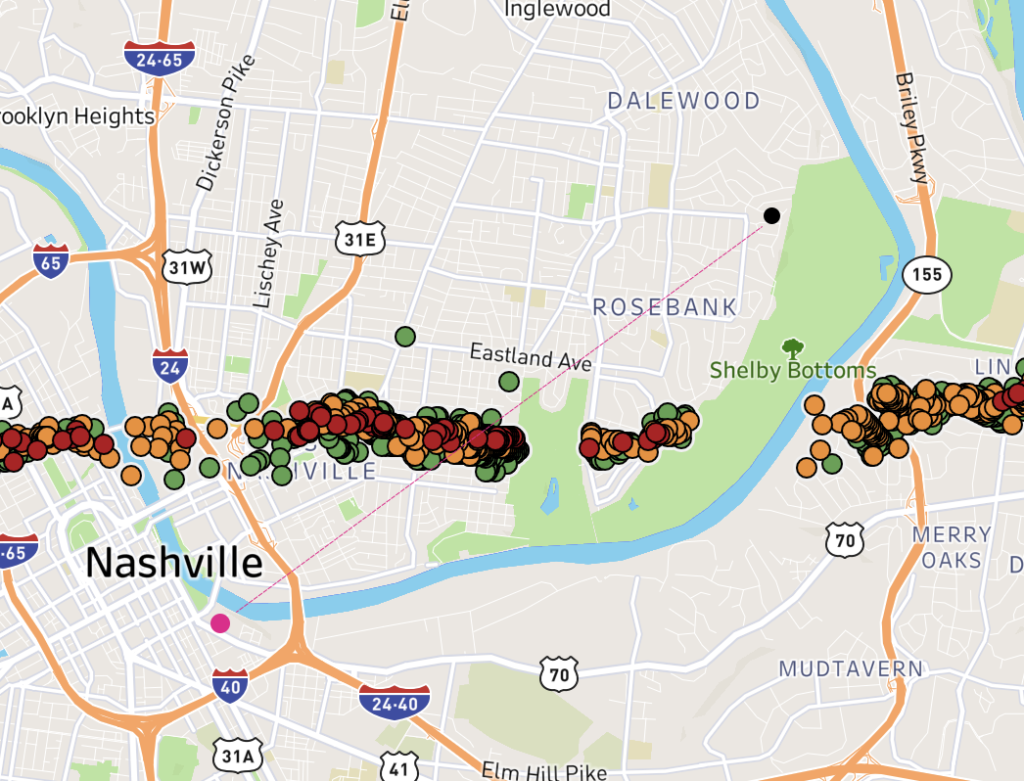

The tornado, I will learn later, once the news reports and infographics start rolling in, cut a wide swath across the city, almost perfectly horizontally, between my destination (pink dot) and our house (black dot).

I phone in to a team conference call so we can go over the latest updates and the plan. We learn that everyone on our team is safe and accounted for. But one of our team members lost her home and another lives in a Donelson neighborhood that was demolished. Somehow, that team member’s house was left standing and had become a hub for water, food, and volunteers overnight. She had been pulling neighbors out of their basements all morning.

[][][]

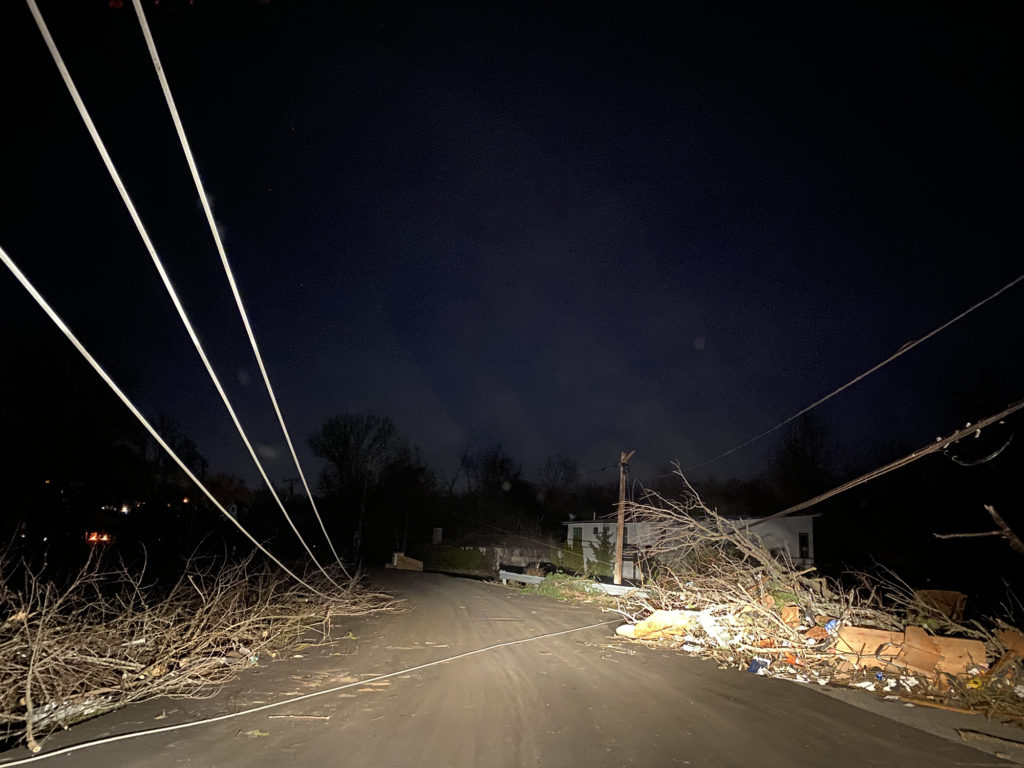

That first night I leave the office around 7:30 and take my chances on my usual commute. The houses along Shelby Avenue are largely dark and the traffic lights are out. I drive through Shelby Park carefully and can’t believe the number of huge trees down. Many of them that had fallen across the road had been cut back so the road is at least passable, although coming out of that road I see that it was blocked to oncoming traffic. I wonder if I am supposed to be there at all.

Riverside Drive heading north is blockaded and service trucks are out trying to dismantle the huge twisted metal transmission tower that had fallen across the road and strewn lines every which way. I detour through the Brittany/Barclay neighborhood, past where my friends Kristin and Lonnie live (they are OK, thankfully, but my God what a close call), and I lose it. I had been in the office all day, frantically answering emails and phone calls and social media inquiries and trying to wrap my head around what was going on. This was what was going on, right in front of me, in pitch black awfulness.

Debris everywhere. Houses with windows and roofs missing. Tarps strung up to help keep the elements out. Trees twisted and splintered. Cars and trucks smashed and crumpled in yards and on the side of the road.

Power lines hang so low across the road I have to carefully maneuver between and around them, unsure if my car can even sneak beneath them.

The abstract is real. Every street I turn down is worse than the next. These are houses I have passed a hundred times on my way to and from gatherings with the people I love. I am sad, I am angry.

I get home and I get back online and I keep working. People have so many questions about how to help and it feels like the thing to do, to help them help. What else can we do?

[][][]

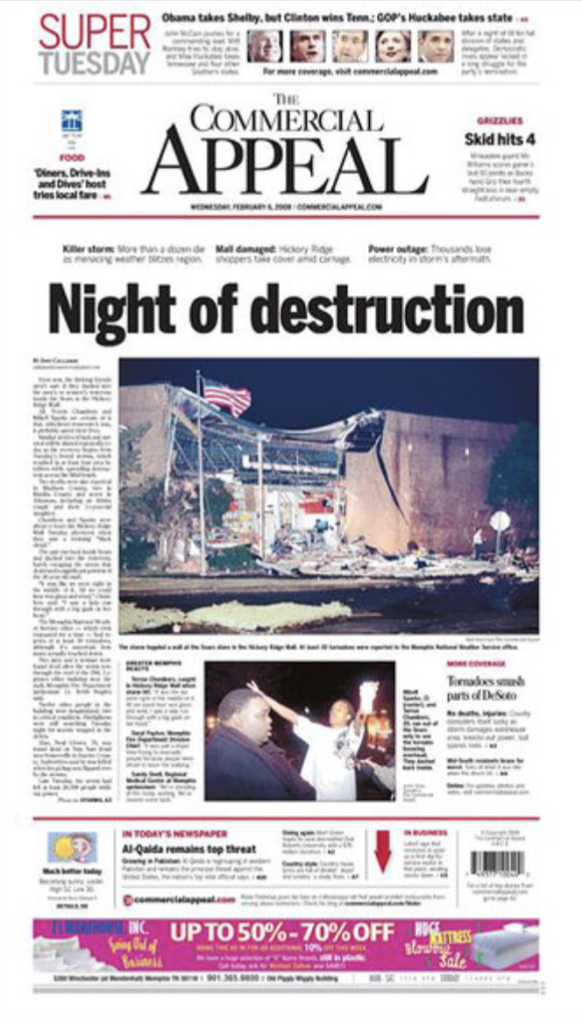

In 2008 I worked at The Commercial Appeal. It was also Super Tuesday — just like March 3, 2020 — and tornadoes swept through the area, walloping the Hickory Ridge Mall. I was designing A1 and we evacuated to the basement during the tornado warning while still being on deadline to get the paper out with tornado news and Super Tuesday results. I remember thinking (and writing) that it was the most stressful night of work I’d ever had.

I can’t even count how many evenings I visited The CA‘s basement during tornado warnings during my seven years there. It just became part of life as a journalist. You didn’t get the day off because of bad weather. You didn’t get to go home early. You showed up and you put the paper out. People needed to know what had happened.

I have thought about the night of the Super Tuesday tornadoes off and on since then, but I never actually thought I’d have to say “Super Tuesday tornadoes” ever again. I’ve got a lot to learn, I guess.

[][][]

Wednesday-Thursday-Friday-Saturday passes in a blur. Our team works around the clock and the days begin to run together. We bring in volunteers to help us manage the insane volume of calls and emails and DMs and comments we’re getting across our social platforms. It’s hundreds, thousands, every day.

Facts on the ground and community needs change quickly, constantly. City agencies reach out to us for help with crowd control and direction as crews move through to reconnect utilities and find themselves unable to get to certain neighborhoods because the streets are choked with the cars of well-meaning volunteers who are just there to help.

Our team laughs when we can, mostly about how we all feel like we’re cracking up a little bit and how time is a construct and all days are just this one long day. We eat whatever is put in front of us, sent by kind and thoughtful people in the community. We try to show each other kindness and grace. Go take a walk, go see the sun, please drink some water, take a half day, nap in my office, log off and pet your dog, read this funny meme. Everyone is working so insanely incredibly hard toward one goal. I feel inspired, amazed, by these badasses around me.

We hear stories of heroism, stories of need, and we work to try to connect the helpers with the people who need them. I talk to reporters and do live appearances on a couple of local and national news channels. I’m honestly surprised I am able to form coherent sentences during these interviews, as I’m barely sleeping and the sleep I do get is fretful.

I barely see my house, my husband, my kid. I get home late and I stay on the computer even later and I get up early and I do it all over again.

There is a special adrenaline that kicks in when you’re trying to help. It’s that plus caffeine that gets me through the first week.

Each night I drive home through the ravaged Shelby/Riverside area and count the orange stickers on the doors of the condemned houses. Each night my breath catches and I don’t make it home without crying. Each night, more and more has been cleaned up and squared away by volunteers and professional crews whose work makes it possible to believe that moving forward is even an option after so much pain.

[][][]

On Sunday, an internet troll makes me cry. I cry in front of my whole team and even a bunch of volunteers — strangers — in the office helping us. “I am so tired,” I say as an explanation. I feel like an idiot because you know who’s tired? Electricians and utility crews, first responders, doctors, nurses. People who don’t have homes. People planning funerals. They aren’t crying about internet trolls, though.

That night I see this Margaret Renkl piece in the New York Times and I cry again as I share it on HON’s Facebook page with a note of my own:

This beautiful Margaret Renkl piece in The New York Times feels like an appropriate end to what has been a devastating, difficult week that was buoyed only by an overwhelming, intense outpouring of love and support from the helpers — YOU. We are all in this together, and life is so short and precious. Be kind. Help your neighbor. Wash, rinse, repeat.

Thank you, Nashville, for all you’ve done this week to help your neighbors dig out and begin to put their lives back together. There will be more work to do this coming week, and the next, and the next. Stay tuned, and we’ll promise to keep you as updated as possible on what’s needed. We are, as always, #NashvilleStrong.

On Sunday night when I log off, I mark 110 hours in my timesheet for the week and I still feel like there’s so much more to be done. Because there is. There is always more to be done.

[][][]

I take Holden with me to work — there’s practically no school all week — and show him what has happened to help him understand why there’s no school, why mom is working 16 hours a day, why things seem so hectic. He doesn’t seem too impressed at first because he has seen much more drastic destruction in superhero movies, where the good guys routinely level skyscrapers in service of the greater good.

The house at the corner of Riverside and Paden is what gets him, though. A huge tree has fallen through the end of the house and is resting in what appears to be a bedroom. I tell him that if you were asleep in your bed and a tree came through the roof and down on top of you, you would likely be very badly hurt or killed. I tell him I’m so grateful that he woke us up that night, because waking up and going to the basement was safer than being in our bedrooms. I tell him we don’t know what happened to the people in that house with the tree in the bedroom. That I hope they are OK but that there were people who died, including some children. I don’t want to scare him but I want him to know that we are at the mercy of nature sometimes. At all times.

He asks questions about how tornadoes form. I tell him about the cool air and the warm air meeting and beginning to dance in a circle that picks up speed and strength. He wants to see videos so I pull up some I’ve seen before on YouTube. He thinks storm chasers are nuts and he is correct.

He asks us to act it out — “you be the cool air and I’ll be the warm air, mom!” — and we spin in circles and then come together and spin as one and we laugh when we get dizzy. It feels absurd and cruel to laugh but, when you think about it, a big finger from the sky touching down and destroying everything it touches seems absurd and cruel too.

We show him an interactive map of the damage so he can understand how lucky we were, how close it came to his friends. How so many places we liked to go don’t exist anymore. His little brow furrows as he downloads all of this information. He gets very worried about Five Points Pizza and is relieved to hear it wasn’t destroyed.

On Monday, a week after the tornado, I’m at work when I get a voicemail from his guidance counselor. We had kept him out of school that day for a couple of doctor appointments. She is calling to make sure he is alive, since she knows we live near the tornado’s path.

My heart breaks, and suddenly I’m in the middle of the office, sobbing at the thought that this question could ever have a different answer. I think about the teachers who called to do wellness checks and never got a reassuring call back about some children.

I’m heartbroken. I’m angry. It feels so stupid to get mad at weather but that’s what I am: Mad at the fucking weather.

[][][]

I’m having another normal day. It’s Sunday, March 15, and I’ve had coffee, bacon, toast. I’ve pet my dogs. I’ve kissed my husband.

Maybe “normal” is not the right word because now the worry about COVID-19 is beginning to catch. Events are canceling, public gatherings are being suspended and discouraged, and people are being told to stay home to stop the spread of the virus.

Now we must figure out how to respond to a disaster in the middle of a global pandemic. People still have urgent needs but it is going to get much trickier to meet them, with supplies running low in some places and people being urged to avoid other people.

We don’t know what will happen with workplaces, schools, anything. It’s technically Spring Break now so we are buying time, but what the next few weeks and months will look like is anyone’s guess.

These are strange times, uncertain times, exhausting times. I hope those who need it most can catch a break soon, I really do.

You must be logged in to post a comment.